Marchese Testaferrata 1717, 1745, 1749.

Last update: 16-04-2023.

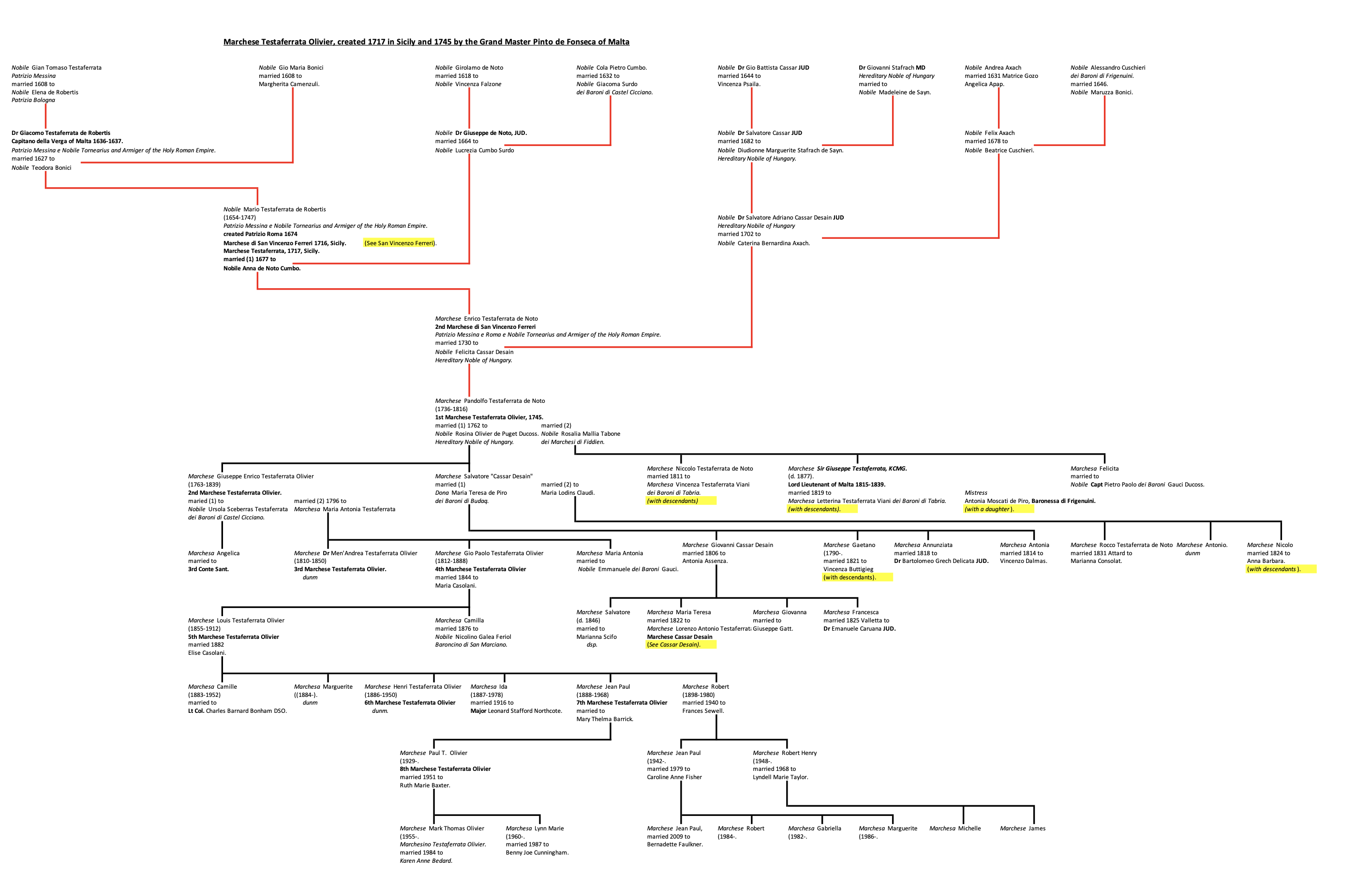

Granted to: Marchese Pandolfo Testaferrata de Noto, (d. 1816).

Title: Marchese Testaferrata.

By: Manoel Pinto de Fonseca, Grand Master of Malta.

On: 1745 in Valletta.

British Crown recognition: 1883.

With Remainder to: Controversies arose between Mario’s descendants from his first and second marriages. It appears that the main dispute was his will opened 9 years after his death and published at Palermo by notary Dixidomino on the 16th April 1758, from which it appears that the said Mario willed as follows:- “in toto integro et indeminuito patrimonio ac in dicto titulo Marchiones Sancti Vincentii nec non etiam in ejus Palatio, etc’ejus haeredem universalem instituit, ac proprio ore nominavit et nominat D. Gilbertum Testaferrata ejus filium”. In the same testament, we find also the following clause: “Et quia dictus illustris testator ultra dictos Dominum Gilbertum et D. Pulchram, ejus filios desuper contemplatos, alium ejus filium primi matrimonii vocatum D. Enricum Testaferrata”. Et pro nonnullis ingratitudinibus disobedientiae, ac pro dubio insidiationis mortis ejusdem testatoris, ut ipse illustris asserit, etiam pro causa dissipationis nonnullorum bonorum mobiliumvigore praesentis, attentis juribus et rationibus desuper descriptis, dictus illus testator eumdem D. Henricum Testaferrata “dishaereditavit, a substantia et patrimonio paterno privando et totaliter eumdem D. Henricum Testaferrata ejus filium tam a successione titolorum Marchionis Sancti Vincentii Ferreri et Testaferrata, quam a succession”..et sic voluit et non aliter nec alio modo, et hoc non obstante quod fuisset per eundem illum testatorem facta wquaedam scriptura private, subscripta propria manu dicti illmi testatoris, in qua declarabat dictum D. Henricum ejus filium, successorem in Marchionem Sancti Vincentii Ferreri.”

List of Title holders:

1. Marchese Pandolfo Testaferrata, (d. 1816), 1st Marchese, succeeded by his son.

2. Marchese Giuseppe Enrico Testaferrata Olivier, (d. 1839), 2nd Marchese, succeeded by his son.

3. Marchese Dr Men’Andrea Testaferrata Olivier, (d. 1850), 3rd Marchese, succeeded by his brother.

4. Marchese Gio Paolo Testaferrata Olivier, (d. 1888), 4th Marchese, succeeded by his son.

5. Marchese Louis Testaferrata Olivier, (d. 1912), 5th Marchese, succeeded by his son.

6. Marchese Henri Testaferrata Olivier, (d. 1950), 6th Marchese, succeeded by his brother.

7. Marchese Jean Paul Testaferrata Olivier, (d. 1968), 7th Marchese, succeeded by his son.

8. Marchese Jean Paul Jr Olivier, (1929-6-8-2021), 8th Marchese, succeeded by his son.

9. Marchese Mark Thomas Olivier, (1955-, 9th Marchese.

Heir: Marchese Jean Paul Testaferrata Olivier, (1942-.

Heir General: Marchese Jean Paul Testaferrata Olivier.

Granted to: Marchese Gilberto Testaferrata Castelletti.

Title: Marchese Testaferrata.

By: Manoel Pinto de Fonseca, Grand Master of Malta.

On: 1749 in Valletta.

British Crown recognition: 1883.

With Remainder to: Che, dall’altro canto, pero’ e’ giusto rimarcare che nella transazione seguita per atti del Notaro Vittorio Giammalvadel 10 settembre 1773 (recte 1772) tra i figli di Don Mario Testaferrata, il primo concessionario del titolo, di cui e’ questione, dopo di avere menzionato solo due titoli di Nobilta’ quello cioe di San Vincenzo Ferreri, e l’ altro di Testaferrata (alledendo a quello conceduto da Vittorio Amadeo) era stato convenuto che tutti i figli con loro discendenti dovessero essere in liberta’ di portare l’ una e l’ atra concessione. (Judgment No. 71/1887 of H.M. Court of Appeal dated 8 January 1887)

List of Title holders:

1. Marchese Gilberto Testaferrata Castelletti, (d. 1774), 1st Marchese, succeeded by his son.

2. Marchese Mario Testaferrata Castelletti, (d. 1813), 2nd Marchese, succeeded by his younger son.

3. Marchese Filippo Testaferrata, (d. 1821), 3rd Marchese, succeeded by his son.

4. Marchese Lorenzo Antonio Testaferrata, (d. 1851), 4th Marchese, succeeded by his son.

5. Marchese Filippo Giacomo Testaferrata, later changed his surname to Cassar Desain (d. 1866), 5th Marchese, succeeded by his son.

6. Marchese Richard Robert Cassar Desain, (d. 1870), 6th Marchese, succeeded by his brother.

7. Marchese Lorenzo Antonio Cassar Desain, (d. 1886), 7th Marchese, succeeded by his son.

8. Marchese Philip Robert Cassar Desain, (d. 1906), 8th Marchese, succeeded by his brother.

9. Marchese Richard George Cassar Desain, (d. 1927), 9th Marchese, succeeded by his son.

10. Marchese James George Cassar Desain, (d. 1958), 10th Marchese, succeeded by his son.

11. Marchese Anthony Cassar Desain, (d. 2000), 11th Marchese, succeeded by his son.

12. Marchese Mark Cassar de Sain, (1965-, 12th Marchese.

Heir: Marchese Max Cassar de Sain, (2002-.

Articles relating to this title:

1. Three Testaferrata de Noto families;.

2. Three Testaferrata Cassia families;

3. Marchese di San Vincenzo Ferreri-non existent ?.

4. Value of the titles usage of dei Marchesi, dei Conti and dei Baroni.

6. Value of the titles of Marchesino, Contino and Baroncino.

7. Title of Marchese di San Vincenzo Ferreri (1716/1725);

8. The Italian title of San Vincenzo Ferreri;

9. Title of Marquis Testaferrata;.

The Italian title of Marchese Testaferrata.

Footnote: The title of “Marchese” was granted at Chambery on the 13th July 1717, to the Maltese Citizen Mario Testaferrata by Victor-Amadeus, King of Sicily and Duke of Savoy. This title did not originate in Malta. At Maltese Law this title is only a foreign title and, as such, it can be considered for the purposes of precedence if registration or Magistral recognition has been achieved in accordance with the rules of 1739 and 1795 as enacted by Grand Masters Despuig and Rohan.

VALUE OF REGISTRATION/MAGISTRAL RECOGNITION From the records of the Cancelleria it appeared that the titles so granted were registered in virtue of a rescript from the Grand Master, on an application by the party concerned. The Royal Commissioners of 1878 remarked that they were prone to believe that the Grand Master would not have given his assent to registration without any investigation. From the start, however, the Commissioners pointed out that the Despuig/Rohan Rules on the matter did not deny nobility to a Titolato who failed to duly register his title, but only assigned him no place insofar as precedence was concerned. (See:- “Correspondence and Report of the Commission appointed to enquire into the claims and grievances of the Maltese Nobility”, May 1878, presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty (C.-2033.) (See Report Paras. 101-102). It is also noteworthy that the Commissioners did not consider all the titles which were registered in the Cancelleria: For example the title ofConte granted to Baldassare Fenech Bonnici on the 11 June 1798 by Pope Benedict XIV, which was duly registered under Archives of the Order of Malta (554, f. 176) as well as the Archives of the Inquisition of Malta (102m f. 32) was not considered by the Report. It appears that no descendant of this grantee made any claim to the Commissioners.

In this case, this title granted to Mario Testaferrata was never registered in Malta, nor does it appear to have ever received direct recognition for the Grand Masters who ruled Malta. (See:- “Correspondence and Report of the Commission appointed to enquire into the claims and grievances of the Maltese Nobility”, May 1878, presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty (C.-2033.) (See Report Paras. 122-172)

Thus, in accordance with the rule cited above, although the title is valid, it does not enjoy precedence in Malta.

It is to be remarked that as at 1878, this title (because of its particularly wide remainder) was claimed by no less than six main claimants, each one backing his respective claim by forceful legal argument. These were Emmanuele Testaferrata Bonici-Asciack, Lorenzo Antonio Testaferrata, Giuseppe Testaferrata Viani, Gio. Paolo Testaferrata Olivier de Puget, Lorenzo Antonio Cassar Desain ne’ Testaferrata and Ignazio Testaferrata Bonici. However, the Commissioners noted that many others could make similar claims.

In addition, it is also noteworthy that the Commissioners remarked that Testaferrata Bonici-Asciack was the seniormost descendant amongst them all. Equally however the same Commissioners noted that if Testaferrata Bonici-Asciack’s line were to be ousted by the grantee’s testament, the title would instead be the entitlement of Testaferrata Viani.

Published sources also show that two of the claimants namely Gio. Paolo Testaferrata Olivier de Puget, Lorenzo Antonio Cassar Desain ne’ Testaferrata were successful in obtaining recognitions extended by Grand Master Pinto of the title under discussion. Indeed, these published sources attribute the dates of 1745 and 1749 respectively as the dates when Grand Master Pinto directly recognized the title granted to their respective forebears. This is manifestly unfounded as the said ‘extensions’ do not refer to the title of ‘Marchese’ granted in 1717 but to another title granted to the same Mario Testaferrata, namely that of ‘San Vincenzo Ferreri’, which is discussed elsewhere. Moreover, it is to be noted that when one of the claimants Emmanuele Testaferrata-Bonici-Asciack subsequently sued both Testaferrata Olivier and Cassar Desain (Judgment No. 71/1887 of H.M. Court of Appeal dated 8 January 1887), the court upheld Emmanuele Testaferrata Bonnici Asciak’s claim that he was to have the exclusive right to the title granted by Vittorio Amadeo, King of Sicily and Duke of Savoy after the same Testaferrata Olivier and Cassar Desain declared “espressamente di essere stato a loro da Sua Maest` la Regina accordato il titolo che portano, e non aggiungendo alcuna pretensione su quello conceduto da Vittorio Amadeo, in sostanza ammettendo la domanda dell’attore di essere egli solo, almeno per quanto concerne loro stessi, nel diritto di portare il titolo di Marchese conferito con quel Diploma”. These declarations positively exclude any link between the title granted in 1717 and the aforesaid recognitions.

The actual report says the following:

“We now proceed to consider the title of ‘Marchese’, granted on the 13th July 1717, to Mario Testaferrata, by Victor-Amadeus, King of Sicily and Duke of Savoy. The patent of creation of this title is worded in Italian, and its operative clause runs thus:- (Translation) “Hence it is that by these presents under our sign manual, of our certain knowledge, Royal authority, and absolute power, and with the advice of our Council we confer as a special favour on the said Mario Testaferrata, and all his legitimate and natural descendants successively, the title of Marquis, with all the privileges, prerogatives, dignities”. “which are or may be enjoyed by other marquises. We therefore command that all our magistrates, ministers, vassals, and all out subjects generally on this and on the other side of the sea”. Shall acknowledge as Marquis the said D. Mario Testaferrata, and his legitimate and natural descendants successively”.

The foregoing grant was made at Chambery, on the 13th July 1717, by the said King Victor-Amadeus, whilst he possessed not only the Duchy of Savoy but also the Kingdom of Sicily. The patent of creation bears the following heading:- “Victor-Amadeus by the Grace of God King of Sicily, Jerusalem, and Cyprus, Duke of Savoy, Montferrat, and Aosta” .and perpetual Vicar of the Empire”; and in conferring the title the King declares that he avails himself of his Royal authority.

It does not appear from any part of the said patent that Victor-Amadeus granted the present title as Duke of Savoy; on the contrary, he thereby ordered that the diploma should be registered in his Principal Secretairerie of State for the Internal Affairs of his Dominions. In pursuance of that command that patent was registered, and not simply recorded in the Registry of the Privileges of the Kingdom of Sicily, and not in the Duchy of Savoy, as stated by one of the gentlemen who claim this title.

In fact, at foot thereof, the following expressions are to be noticed:- “Reg. in Regio. Privil. Regn. Sicil., fol. 180, No. 1 (signed) Razan.” The concluding words of the patent, on the other hand, “Given at Chambery, on the 13th July, in the fourth year of our reign”, clearly shows that Victor-Amadeus did not grant the title either as Duke of Savoy or as Vicar of the Empire, for his accession to the throne of Savoy took place in 1675, that is 22 years previous to the said grant; but as King of Sicily, this island having been ceded to him by the treaty of Utrecht, concluded on the 11th November 1713. that is four years before he conferred the title in question.

We have entered into all these particulars, because some of the gentlemen who claim the right of simultaneously enjoying the title we are considering have based several of their arguments on the hypothesis that the extension of that title is to be regulated by certain principles of feudal law, which at the time of the grant obtained in Germany, Lombardy, Savoy, and in other parts of Italy, and by the so-termed custom of the Longobards.

The title is claimed by several gentlemen who assume that it is descendible to all the grantee’s contemporary lineal successors, and not to the first-born son exclusively, under the rule of primogeniture. If the title, however, is taken to extend to all the contemporary descendants of the person first ennobled, many other gentlemen who, like the claimants, are the descendants of Mario Testaferrata, would be equally entitled to the enjoyment of the present dignity.

The number of such descendants, according to a table of descent which we have caused to be prepared by a genealogist, and which is appended to this report, amounts to No. 157.

In this number we have also included the female descendants and the male descendants of the daughters for if the grant is held to be so unlimited as to include all the grantee’s descendants without any restriction, female descendants cannot by logical inference be excluded form the possession of the title. King Victor Amadeus himself in the grant of the title of Conte, conferred upon Giuseppe Preziosi, on the 19th October 1718, wishing to exclude from the succession of the grantee’s female issue, ordered that the title was “to hold to the grantee and his legitimate and natural male descendants, in lawful wedlock begotten, whether born or to be born.”

Of daughters and the male issue of daughters are not comprised in the present grant, the number of gentlemen who would be entitled to possess the dignity now inquired into would be 24. The children or descendants who under such construction might claim the title after the decease of their ancestors and who have not appeared to claim it themselves are 93 in number, including all the female descendants; but if the latter be excluded, that number would be reduced to 51.

But the present inquiry involves an important question on the settlement of which the existence of the title thoroughly depends. It is necessary to ascertain before-hand whether the title has ever lawfully existed in Malta, that is, whether it was either registered in the Government Cancelleria and in the High Court of the Castellania, or otherwise recognized by the sovereign authority in Malta. With reference to this question, it is to be remarked that the patent containing the grant was never registered in the Cancelleria or in the Court of the Castellania, not even after the publication of the decree issued by Grand Master Despuig, notwithstanding that all the foreign titles granted previous to the said decree of which we have any notice were regularly entered in the records of the said two offices, with the exception of those of Barone di Cicciano and of Marchese di San Vincenzo Ferreri, the last mentioned titles having been, however, unquestionably recognized prior to 1725. The patent was only recorded in the acts of Notary Carlo Caruana on the 21st April 1731, in order to ensure its preservation. Such record, however, would not have certainly hindered nor dispensed with the registration prescribed by the said decree if the Grand Master had authorized it.

Some observations having been made to the Commission with respect to the necessity of the enrolment of the patent, we feel it our duty to consider and resolve the question whether it was necessary that the present title granted by Victor-Amadeus as King of Sicily should have been registered or otherwise acknowledged by the Grand Masters, to whom the islands of Malta were granted in fee by the Kings of Sicily. The Order of St. John after its expulsion from the island of Rhodes, where it had since a long time been established, obtained, as already stated (#20), by a patent given at Castelfranco, on the 24th March 1530: “in feudum perpetuum, nobile, liberum, et francium, civitates, castra, loca et insulas nostras Melitae et Gaudisii cum omnibus ipsarum civitatum, castrorum, locorum et insularum territories jurisdictionibus, mero et mixto imperio, jure et proprietate utilis dominii ac gladii potestate, hominibus et foeminis in eis et earum terminis habitantibus et habitaturis, cujuscumque legis, status et conditionis existent, omnibusque aliis juribus et pertinentiis, exemptionibus, privilegiis, proventibus, aliisque immunitatibus”..ita ut hujusmodi feudum deinceps teneant et cognoscant a nobis tamquam Regibus Siciliae Ulterioris et a successoribus nostris, in eodem Regno pro tempore regnantibus, seb censu dumtaxat unius accipitris seu falconis quolibet anno praesentandi. The other conditions attached to the grant regarded the oath of fealty, the investiture, the patronage of the bishopric, the extradition of certain refugees, the observance of the privileges previously conferred by the grantor and his predecessors, and the reversion of the fief to himself and his successors in case the Order should either recover Rhodes or lease Malta, or fix elsewhere its residence. And in order that the grantee and his successors might hold and possess the said islands, exercise all kinds of jurisdiction over the same, and rule them perpetually and peacefully, it was added in the patent: Damus, cedimus et donamus dicto Magno Magistro conventui et religioni omnia jura, omnes actions reales et personales, et alias quascumque quae nobis competent et competere possunt et debent in praedictis quae illis in feudum praedictum sub dictis conditionibus concedimus, etc” Et ponentes dictum Magnum Magistrum, conventum, et religionem, in praedictis omnibus et singulus in locum et vices nostras, constituimus eos verso dominos utiles” nullo jure nullaque actione utili, in praedictis quae illis concedimus, praeter superius reservata nobis aut curiae nostrae, modo aliquot retentis et reservatis” Mandantes serie cum praesenti, eadem auctoritate nostra, universes et singulis homnibus masculis et foeminis” in dictis insulis, civitatibus .dictum Magnum Magistrum conventumque et religionem pro eorum domino utili et feudali, ac vero possessore omnium praedictorum habeant et reputent: suisque mandates pareant et obedient.. Nos etiam nunc pro tunc..absolvimus et liberamus eos ab omni juramento et homagio quod nobis nostris ac predecessoribus, aut aliis personis nominee nostro fecerint et praestiterint obligatique fuerint. The foregoing are extracts from an authentic copy of the bull or grant existing in the Cancelleria. From the above extracts it appears that Charles the Fifth ceded and granted in absolute fee to the Grand Master and his religious Order the islands of Malta, and Gozo, with all the rights of property annexed thereto, for the purpose of having, holding, and ruling them peacefully and perpetually, and of exercising therein all jurisdiction, and with the exception of the rights specified therein, he did not reserve to himself and his court any right or dominium utile. He at the same time commanded all the inhabitants of the said islands to acknowledge as their sovereign the Grand Master and his convent, and exonerated and absolved them from any oath of allegiance taken unto himself and his predecessors.

It therefore follows that the King dispossessed himself of his sovereign authority, which was thoroughly vested in the Grand Master and his Order; these he appointed and constituted in his stead, and thus he became with regard to the government and administration of these islands almost a foreign sovereign.

Considering the aforesaid facts, the mutual relations between the grantor and the grantee, and the object for which these islands were granted to the Order of St. John, we submit that the rights inherent in the high or the directum dominium, which according to the terms of the patent the Emperor reserved to himself, could be exercised only in the cases specifically laid down in the deed of donation. Now, among the conditions under which the grant was made, there is no one providing that all the laws which the Emperor would have enacted, and the privileges he would have conferred as King of Sicily, should be recognized and enforced in the territory he had granted to the Grand Masters and the Order of St. John.

But even if ex hypothesi, in virtue of the high dominium vested in the successors of Charles the Fifth, a privilege granted by a King of Sicily was to be taken to be equivalent to a privilege conferred by a local sovereign, yet in the grant we are considering, King Victor-Amadeus, one of the successors of Charles V, on the throne of Sicily, did not specify in the patent of creation that he conferred the title by virtue of the rights which belonged to him on the island of Malta.

One of the gentlemen who claim the present title, Gio. Paolo Testaferrata Olivier, in a memorandum headed “Second Statement of Law and Fact”, refers to a Declaration of Philip II, which on slight examination may be retorted against himself. Philip II, by that declaration, which as King of Sicily Ultra he issued at Brussels on the 27th June 1559, referring to the deed of grant made by Emperor Charles V to the Order, definitely enacted, “in dicto privilegio concessionis et donationis Insularum Melitae et Gaudisi, fuisse et esse concessas et comprehensas cognitions et totales decisions causarum pheudalium et earum appellationem, cujuscumque generic et qualitatis sint, caeteraque omnia Regalia praeter ea quae in ipso privilegio expresse excipiuntus, et hanc fuisse et esse mentem et volontatem Imperatoriae Regiae Majestatis et nostrum, et quatenus opus sit de novo concedimus, et elargimus non obstantibus”

The said Gio Paolo Testaferrata contends that before the foregoing declaration, the Grand Masters were bound to refer to the Kings of Sicily the cognizance and decision of feudal suits; an assumption which, in our opinion, is in direct opposition to the plain wording of the said deed, which entirely removes the any doubt that might be raised as to the necessity of the registration of the grant now under consideration.

(Commissioners “description of Claimants” claims)

We next come to enquire whether, in the absence of a regular registration, there can be said to exist on the part of the Grand Masters of the Order any acts of recognition of the present title, either in the person of the original grantee or in that of his descendants. On this point no documents have been exhibited except by the claimants Gio Paolo Testaferrata Oliver and Lorenzo Cassar Desain.

(Claim of Gio. Paolo Testaferrata Olivier)

The former of these gentlemen has laid before us several papers, among which there is a certificate from Notary Giuseppe Bonavita, stating that in the acts of Salvatore Ignazio Bonavita (of which acts the said Giuseppe was conservator) there existed a marriage contract received by the aforesaid Notary Salvatore Ignazio Bonavita, on the 26th April 1762: “inter Illustrissimam Dominam puellam virginem, etc”. spousam ex una parte, ac inter Illustrissimum Dominum Nobilem Tornearium Sacri Romani Imperii, Marchionem Don Pandulphum Testaferrata filium legitimum et naturalem quondam Illmi Dni Marchionis Sancti Vincentii Ferreri Don Henrici Testaferrata et Illustrissimam Dnam Marchionissam D. Felicitam Cassar Testaferrata” .sponsam ex altera. The object of the production of the said document is clearly evinced by the following annotation contained in the above-mentioned memorandum presented by claimant Gio Paolo. “Certificate of the marriage of the aforesaid Pandolfo, with the authentication of Chancellor Ferdinando Hompesch, who was subsequently elected Grand Master, in which certificate Pandolfo is recognized as Marquis. Doc. 5”. We were, however, unable to find out in that document that the Chancellor of the Order, on behalf of the Grand Master, has thereby confirmed and attested the declarations contained in that certificate, or acknowledge, that Pandolfo was really a marquis. On the contrary, it appears from that document that the Vice-Chancellor of the Order, under the Grand Mastership of the said Hompesch, referring only to the signature of the above-mentioned Notary Giuseppe Bonavita, has made the following declaration: “Fr. Ferdinandus de Hompesch, Dei gra Domus Hosplis Sti Joannas Heerni. “Magister humilis” Notum facimus et in verbo veritatis attestamur qualr Joseph Bonavita qui retroptis se subscripsit, publicus legalis et fidedignus nots fuit et est; cujus actis, scris et instris publicis, simper adhibita fuit et in dies adhibetur plena et indubitata fides. In cujus rei Testimonium, Bulla Nosta Magli in cera nigra pntibus est impressa. Dat. Melitae in Contu Nostro, die 18 mensis Aprilis 1798.” This attestation, which in substance is nothing but an authentication of the signature of the notary who extracted the above-mentioned certificate from the acts of another notary, is precisely similar to six other attestations of an equal number of notarial certificates, which attestations were made in the name of Grand Master Hompesch. These certificates have been exhibited for the object of proving in part the pedigree of the said Gio Paolo. We must, however, observe that one of these documents is a duplicate of the certificate we have already considered, and bears the same date.

Another document called by the claimant who produces it “Sentence of the Senate of Messina”, dated the 18 August 1793, and laid before the Commission by G.P. Testaferrata, contains the following address: “Marchionibus D. Mario Testaferrata Castelletti, D. Danieli, et. D. Pandulfo Testaferrata de Noto germanis fratribus, sacri Romani Imperii Equitibus Torneariis”. In this document the following expressions occur: “praeter alios honorum titulos Marchionatus Sancti Vincentii Ferreri tessera in Regno Neapolitano decorate, alioque etiam Marchionatus titulo insignita in Regno Neapolitano decorate, alioque etiam Marchionatus titulo insignita, a Victorio Amadeo Savando tum rege nostro gloriosissimo”, .et sedulo quoque animadversis majorum nostrorum meritis erga Siciliae regnum nostrosque augustissimos Reges, quae merita resultant ex actis legitime exhoibitis ex historiarum fide, ex publica fama, atque ab ipsismet Regiis Diplomatibus. Vos praedictos illustres Marchiones D. Marium Testaferrata Castelletti, D. Danielem et D. Pandulphum Testaferrata De Noto Germanos fraters. propria aitaque virtute praeclaros, antique nobilique tum Romano tum Messanensi genere procreatos, in verso et indubitatos nobiles cives Patriciosque nostros ex prisca origine recognoscimus, acceptamus, recipimus et amplectimur. The local sovereigns, as far as we are aware, never recognized the distinction conferred by the foregoing grant, either by authorising its registration or by other acts from which their intention of approving it might be safely inferred. But as the document in question has been produced in order to show the grant we are inquiring into admits of an extensive construction, we think it expedient to submit, on this point, the following remarks:- The Senate of Messina undoubtedly styles marquises three persons of whom one alone was the first-born descendant in the primogenial line of the Testaferrata family. But even if that Senate were a competent authority for interpreting the deed of grant made by Victor-Amadeus, no such interpretation appears to have been given by that body. The aforesaid diploma thus alludes to the nobility of the Testaferrata family: “Alios honoris titulus Marchionatus Sti. Vincentii Ferreri tessera in regno Neapolitano decorate, alioque etiam Marchionatus titull insignita a Victorio Amedeo Sabando tum Rege Nostro gloriosissimo”. That diploma was, on the other hand, intended to raise to the Messinese nobility the said Mario, Daniele and Pandolfo, an not to construe the grant made by Victor-Amadeus. Hence it follows that the expressions “Marchionibus D. Mario Testaferrata Castelletti, D. Danieli, et D. Pandulpho Testaferrata De Noto” and those “Vis praedictos illustres Marchiones D. Marium etc.” are thoroughly inoperative, and cannot reasonably be taken to furnish an extensive construction to the grant we are considering.

The foregoing remarks will also apply to the following documents exhibited by the same claimant G.P. Testaferrata Olivier, viz:- 1st A certificate of the aforesaid Senate of Messina, bearing date the 12th July 1791, by which it was attested (Translation from the Italian) “To whomsoever these presents shall be exhibited, whether in judicature or thereout, whether in the Kingdom of Sicily or elsewhere, that the family Testaferrata of Malta, from whom Marquis Errigo Testaferrata dei Marchesi di San Vincenzo Ferrerri, dei Conti de Puget, a nobleman of the Holy Roman Empire (the claimant’s father) descends, is a noble and patrician family of this city (and has been so) since the year 1553, in virtue of a privilegium granted to Mariano Testaferrata, as appears from Il Libro Diverso of the year 1553”..; 2nd Three passports, the first of which was issued by Mse. Domenico Caracciolo, Minister for Foreign Affairs of the King of the Two Sicilies, on the 8th May 1789; the second was given at Rome, on the 30th August 1789 by Chev. Giuseppe Ricciardelli, Charge d’Affaires of the same King at the Court of Rome, and the third was delivered by Chev. Giovanni Acting Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs of the aforesaid King, on the 7th January 1790. The first of these documents runs thus: “Whereas Marquis D. Enrico Testaferrata, a Maltese aged 31, is about to leave for Rome etc”. In the second we read: “Whereas Marquis Don Giuseppe Enrico Testaferrata of Malta is on the point of starting from this Court,” and in the third “Whereas Marquis Testaferrata, aged 34, common sized, is about to leave for Malta his native country, etc.”

The claimant G.P. Testaferrata Olivier has moreover produced sixteen other documents accompanying the memorandum already referred to, and which contains some additional observations and authorities intended to establish the claimant’s right to the present title. Some of these documents (which will be considered hereafter) refer to the period during which these islands have been possessed by the British Crown; whilst others relate to a more distant period, and are the following: -1st. An order issued by General Bonaparte, after the occupation of Malta by the army of the French Republic, on the 28th Praireal in the 6th year of the Republic, by the 5th Article of which it was prohibited to whomsoever to bear feudal titles; 2nd Another order issued by Bosredon Ransijat, President of the Government Commission (Commission du Governement) on the 6th July 1798, by which it was enacted that all honorary titles should be burnt, on the 14th of that month, which was the day of the National Feast (Fete Nationale), and that every holder of a title should carry his patents at the foot of the Liberty pole (Arbre de la Liberte’). It is not easy to conceive how these two documents can bear upon the subject we are considering. 3rd. An authentic copy of the letters patent by which King Victor-Amadeus, on the 13th July 1717, conferred the title of Marquis upon Don Mario Testaferrata and all his descendants (for an extract from this diploma se paragraph 123). This same document clearly shows that the said diploma was granted by Victor-Amadeus as King of Sicily. At the foot thereof, in fact, we read: “Collatum cum Litteris. Patentibus descriptis in Registro Privilegiorum Regni Siciliae quod servatur in hoc Regio Archivio Taurini, die 10 Julii 1798. Carolus Franchi Vice Custos Regii Archivii.” 4th A copy of the Prammatica issued by Grand Master Manoel on the 20th April 1725 and of the decree of the 9th July 1725, to which we have already referred (#94). By the latter of these enactments, Don Mario Testaferrata was recognized as Marchese di San Vincenzo Ferreri, and not as Marquis, in virtue of the grant made by Victor-Amadeus and upon which we are reporting. 5th A duplicate extract from a marriage contract, bearing date the 22nd January 1730, in which Enrico Testaferrata styles himself Marquis, and his father Mario is designated as “Marchese di Testaferrata” 6th A certificate from the parish priest who assisted, on the 28th April 1762, at the marriage ceremony of Pandolfo Testaferrata, therein styled as Marquis, and son of the late Enrico, Marchese di San Vincenzo Ferreri. This document and the preceding one do not contain any direct or indirect recognition of the title of Marquis on the part of the sovereign authorities. 7th Five documents signed by private individuals in the years 1797 and 1798, declaring that the Testaferrata family, to which (as it is therein written) Marchese Giuseppe Enrico Testaferrata belongs, hold, in their own right, several graves and armorial ensigns. It is hardly necessary to observe that these declarations can give no particular title of nobility; nor can we conceive why Giuseppe Enrico Testaferrata, the claimant’s father procured these certificates from private individuals towards the end of the 18th century.

These are the documents which, together with a copy of a deed of transaction and of a bull containing the appointment of Enrico Testaferrata, senior as one of the Jurats (which latter documents will be subsequently considered), have been laid before the Commission by the claimant Gio. Paolo Testaferrata, and most of which have reference to a period during which the Order held the sovereignty of these islands. After a careful consideration of these documents, we are of the opinion that they do not prove the recognition alleged by the claimant, or at least the concurrence of such requisites as are necessary for holding that the sovereign’s assent in the possession of the title of Marquis; and that such possession was lawful, that is constant, uniform, and unequivocal.

We must here submit that in a document existing in the Archives, and containing the list of the Jurats of Notabile, and in another in which the appointment of those functionaries was annually entered, we find that in the year 1778-1779, the title of Marquis was given to Enrico; but of that title no mention is made in the Minute Book (Libro delle Minute), the official record in which the appointment of the Jurats was registered; and in the years 1793-1794, and 1794-1795, that is three years previous to the fall of the Order, the name of Enrico, who again was appointed to the Juratship, is not preceeded, in the important Minute book and in the Register of the University, by the title of Marquis, but accompanied only by the designation “dei Marchesi” (The expression “dei Marchesi”, which occurs here and in other parts of this Report, is a designation borne between the Christian name and surname of those persons who belong to a titled family, but who do not enjoy themselves the title, which is possessed by another member in the family. It corresponds to the Latin phrase e marchionibus, but no equivalent exists in the English Peerage law language). It is also by the expressions: Nobile Giuseppe Enrico Testaferrata de Marchesi di San Vincenzo Ferreri that several years before, in 1787-1788, the aforesaid Enrico was designated, although nothing on the subject is written in the Minute Book.

It is moreover to be remarked that in 1788, and for several subsequent years, Pandolfo Testaferrata, father of Enrico, was yet alive; that even if the grant made by Victor-Amadeus is to be taken to extend to all the descendants of Mario Testaferrata, the succession to the title must, according to the terms of the patent, proceed in a successive order; and that, consequently, the title cannot be borne simultaneously by the father and the son; so that Enrico could not assume it during his fathers lifetime. If the title therefore was given to Enrico before his father’s decease, it must be presumed that the person who gave that title was acquainted neither with the terms of the grant nor with the condition of Enrico at that time.

The foregoing remarks lead to the conclusion that the title of marquis must be considered as having been erroneously given in the abovementioned-certificate of the Senate of Messina, and in the aforesaid three passports given by the Neapolitan authorities to Enrico previous to the death of Pandolfo.

Under these circumstances, we think that there are sufficient grounds for holding as utterly irrelevant the fact, that in the above-mentioned bull produced by the claimant Gio Paolo, the title of marquis was prefixed to the name of the said Enrico Testaferrata, senior, his ancestor, on the occasion of his appointment to the Juratship made by Grand Master Manoel in the year 1735. Mario Testaferrata died in 1747. Consequently the designation of marquis could not but improperly and erroneously have been given to Enrico in 1734.

There is, however, no reason for holding that by designating on those occasions Enrico as marquis, reference was made to the title of marquis granted by Victor-Amadeus, a title which does not appear to have ever been taken into consideration by the Grand Masters in their official acts or records. On the contrary, it seems probable that the title of Marchese di San Vincenzo Ferreri, which was formally recognized by the Prammatica of the 30th April 1725 and by the subsequent decree of the 9th July of the same year, was thereby alluded to. Again, if Grand Master Manoel had ever recognized the title we are considering, he would not have omitted to mention it in the aforesaid decree of the 9th July, and would not have accepted from the enactment of that Prammatica Mario Testaferrata, by styling him only as “Marchese di San Vincenzo Ferreri”. The title under consideration existed at that time, it having been conferred by King Victor-Amadeus in the year 1717, that is, eight years before the publication of the said Prammatica.

(Claims of said Gio. Paolo Testaferrata Olivier and Lorenzo Cassar Desain)

The two claimants, Gio Paolo Testaferrata Olivier and Lorenzo Cassar Desain have, as already stated, produced a copy of a deed of transaction received by Notary Paolo Vittorio Giammalva (It is worth noting that in G.P. Testaferrata’s memorandum it is stated that the said deed was published in the presence of the Judge of the Court of Voluntary Jurisdiction, whereas form no part of that instrument it appears that the said Judge was present at its execution.).

We must state, on this point, that on the 10th September 1772, after the death of Mario and of Enrico, his first-born by Anna De Noto his first wife, Enrico’s sons Daniele, Pandolfo and Asteria, on the one part, and Gilberto another son of Mario by Elisabetta Castelletti his second wife, on the other, after having brought against each other various suits, which were begun during the lifetime of Enrico, and were decided by the Rota Romana, agreed to compromise all matters between them.

In order to stipulate this deed, there appeared Daniele in his own name and on behalf of his brother Pandolfo, and of his sister Asteria, wife of the Barone Giovanni Francesco Damico Inguanez, and Mario Testaferrata, son of Gilberto, as procurator of his father, and among other clauses, the following was agreed to:-Praefati quoque Dni contrahentes pro se et suis, convenerunt et convenient quod tam memoratus Dnus Don Gilbertus, ac sui filii et descendentes in infinituum, quam preti Dni Daniel, Don Pandulphus, et Donna Asteria eorumque filii et descendentes in infinitum, reciproce ac unite uti possint uti possint titulis omnibus honorificis atque nobilibus familiae competentibus, ac segnantur titulis Marchionatus Sancti Vincentii Ferreri et Marchionatus de Testaferrata et Equitis Sacri Romani Imperii, quorum copia uni alteri consignare debet, aliisque juribus etiam patronatus simplicis familiae competentibus et non aliter.

This is the so-termed patto di famiglia (Anglice, family compact), which after the death of Mario was entered into, and by which also Asteria, a daughter, and her descendants were admitted to bear all the titles belonging to the family, that of Marchese De Testaferrata included. But is the latter title, De Testaferrata, proceeding from the grant made by Victor-Amadeus, is not to be taken to extend to all the contemporary descendants of Mario, and if, whatever may be its extension, it was neither duly registered in these islands nor acknowledged by the local sovereigns, it is clear that the afore-said agreement is legally null and void.

Whatever may be the effects which similar agreements may produce between the contracting parties, on which point we shall not offer any remark, it is an unquestionable principle of law that titles of nobility, as they affect social order must exclusively proceed from the Crown, from which all honours and distinctions must emanate. We cannot therefore, assume, that titles, such as the one we are considering, can be lawfully explained, construed, or extended by private agreements.

(Claims of said Gio. Paolo Testaferrata Olivier, said Lorenzo Cassar Desain and Emmanuele Testaferrata, Ignazio Testaferrata, Barone Dr. Giuseppe Testaferrata, Lorenzo Antonio Testaferrata, Enrico Testaferrata and Luigi Testaferrata)

The other gentlemen who, besides Gio Paolo Testaferrata Olivier, claim the present title are Emmanuele Testaferrata, whose name has been often referred to in the foregoing paragraphs of this Report; Ignazio Testaferrata his brother; the Barone Dr. Giuseppe Testaferrata; Lorenzo Antonio Testaferrata; and Lorenzo Cassar Desain. All these gentlemen are included in the Committee list. In the course of our inquiry the following gentlemen appeared to claim, as they expressed themselves, “the title which respectively belong to them”

The said Emmanuel Testaferrata and his brother Ignazio descend from Enrico Testaferrata, senior, first-born son of Mario, senior.

The Barone Dr. Giuseppe Testaferrata is the first-born descendant in the primogenial line of Gilberto, second-born son of Mario, senior.

Lorenzo Antonio Testaferrata and Luigi his brother descend from Lorenzo Testaferrata, second-born son of Mario, junior, who was born of the said Gilberto.

Lorenzo Cassar Desain, and Enrico Testaferrata, his uncle, derive their descent from Filippo, younger son of the said Mario, junior.

Emmanuele is, moreover, the first-born son in the descending line of Enrico, and he would undoubtedly be entitled to the enjoyment of the marquisate if this title legally existed, and if he could not be ousted from it by the paternal testament.

With regard to the claims of all the aforesaid gentlemen, we cannot but come to the same conclusion at which we arrived after having inquired into the claims of Gio Paolo Testaferrata.

We only beg to add that if the title subsists, and if it is to be taken to extend to all the contemporary descendants of the original grantee, all the said claimants like Gio Paolo, would have the right of bearing simultaneously the present title. And under such construction, if all those claimants, most of whom are not the first-born descendants in the direct lines of the grantee, or do not descend from his first-born son, are entitled to the joint possession of the dignity we are considering, many other persons who belong to the same family, and who, as far as we know, have never asserted their claims to this title, would as a matter of course, have the right of enjoying it.

But if, on the contrary, the title lawfully subsists, and it is inheritable by the first-born son only, under the rule of primogeniture, the marchese would be the said Emmanuele Testaferrata, should the disinheritance in Mario’s testament be void, but, if valid, the title belongs to the said Dr. Giuseppe Testaferrata.

(Further considerations on claims of said Lorenzo Cassar Desain)

As we have before remarked, all the arguments which have been adduced with respect to G.P. Testaferratas claim, will apply equally to the claims of the other gentlemen, who Lorenzo Cassar Desain alone excepted, have not produces in support of their respective claims any other documents but their genealogical trees with several proofs of their descent. Among the documents produced by Lorenzo Cassar Desain, relative to the recognition of the title, we find a copy of the diploma of Victor-Amadeus, another diploma of the Senate of Messina, and a copy of the deed of transaction received by Notary Giammalva. Our remarks on these documents have already been submitted in the foregoing paragraphs of this report.

The said claimant has also produced a genealogical tree showing his descent form Mario Testaferrata. He has likewise exhibited two papers containing several quotations from feudal writers, and an extract from the deed of foundation of the Primogenitura Cassar Desain; which last-mentioned document he produced in order to justify the change of his rightful family name Testaferrata into that of Cassar Desain.

Lorenzo Cassar Desain, who is a descendant through a male line of Mario Testaferrata, has like his deceased father, dropped the name Testaferrata and assumed that of Cassar Desain, in order to be able to possess the aforesaid Primogenitura, which was instituted by Gio. Battista Cassar Desain in his testament received in the acts of Notary Paolo Vittorio Giammalva, on the 7th April 1781. That testament contains, among other disposition, the following clause (translated from the Italian):- “I further direct and expressly command that the possessor of the said Prmogenitura erected, as herein-before stated, by me, shall always bear the name Cassar Desain, without adding any other family name thereto, and that he shall, at the same time, bear the armorial ensigns of the said family Cassar Desain, under the penalty of forfeiture, upon breach of the said condition, and my will is that, in such case, the said Primogenitura shall forthwith go to and be vested in, such person as should have succeeded to it, after the death of such defaulter, and not otherwise.” With reference to the foregoing extract we beg to state that the family of which the said Lorenzo Cassar Desain is bound to bear the surname and armorial ensigns is not in possession of, nor has it ever asserted any claim to, any title of nobility.

After having submitted the reasons alleged by the claimant in order to establish the recognition of the present title, we feel it our duty to state, that from the Records of the Government Archives, it appears that in 1749 and 1750, Gilberto Testaferrata, and Mario his son, in 1776 and in 1777 were styled Marchesi, when appointed Jurats by the Grand Masters. Their appointment is regularly entered in the Minute Book. But any presumption arising from these facts is greatly weakened by the circumstance that, in subsequent years, Mario was not designated by the title of Marchese by the Grand Masters. He was in fact reappointed Jurat foe the years 1778-1779 and 1779-1780, and although on that occasion in the list of Jurats, and in the Records of the Universita which were not compiled under the authority of the Grand Masters, the title of Marchese appears to have been prefixed to his name, yet in the bull only the designation of nobleman was given to him.

We have not been able to discover why in 1749 the title of Marchese was given to Gilberto; this circumstance may be only explained by supposing that the suppression of the title previously given to Mario, who in 1778 and 1779 was in the same condition as Gilberto his father in 1749 (Gilberto died on the 10 August 1774), took place in consequence of a careful examination into the terms of grant and that the local sovereigns apprehended lest the precedent laid down on that occasion should carry with it the acknowledgement of the title in the person of the descendants who did not belong to the grantee’s primogenial line. Our assumption is supported by the circumstance that the title of Marquis was withheld not only in 1778, but also in 1779; nor can its omission in the former year be attributed to an unintentional error on the part of the Grand Master, for in such case Mario would in 1779 have applied for and obtained the reinsertion of this title and the reintegration of his rights.

It is moreover to be noticed that in the Bull by which the Grand Master’s assent was given to the appointment of the Jurats for 1778-1779, all the titled gentlemen on whom that office was conferred, together with Mario, were properly designated by their respective titles. This we find that with the nobleman Mario Testaferrata, Barone Francesco Bonici was appointed Jurat in 1778, and his appointment was confirmed in 1779, and Barone D. Pasquale Sceberras, who had been elected Capitano della Verga in 1775, 1776 and 1777, was reappointed to that office in 1778, and his appointment confirmed in 1779.

Nor can it be affirmed that, because Gilberto and his successors possessed the title for a certain space of time, the claimant’s right had been established in virtue of prescription, for even admitting their assertion that titles of nobility may be acquired by a possession of 30 years, no prescriptive right may be claimed on this occasion, inasmuch as from 1749, when the designation of Marchese was given to Gilberto, to 1778, when that title was withheld, no uninterrupted possession appears to have been enjoyed for the term of 30 years.

Having premised these circumstances we think that the gentlemen who appeared to assert their rights to the present title have failed to show that those under whom they claim were under the government of the Order lawfully recognized as Marchesi by the sovereign authorities of the island.

(Considerations on further documents presented by said Gio. Paolo Testaferrata Olivier)

Gio Paolo Testaferrata and Lorenzo Cassar Desain have produced several other documents to prove that the title has been recognized by Her Majesty’s Government.

It is not our province to express any opinion on the import of the acts by which those claimants have endeavoured to establish a recognition of their title. The Right Honourable the Secretary of State may perhaps form a correct opinion on some of these documents, and on some others the local authorities may furnish his Lordship with full and reliable information.

The first of these documents is a warrant of diploma whereby Henry Pigot, Major-General of His Majesty’s forces, appointed on the 1st January 1801 the said Enrico Testaferrata, junior, to be captain of the militia. That warrant (of which the following is a translation from the Italian original) rusn thus: “By virtue of the authority with which we have been invested we nominate and appoint you, Marchese Giuseppe Testaferrata, captain of the division of the militia in this island of Malta of which Conte Luigi Ma. Gatto is the commanding officer.” This warrant is signed thus: ‘H. Pigot, Mr General’ and ‘by order of his Excellency the Major-General John Dalrymple, A. Adjt. Genl.’

The following are the other documents presented by the claimant Gio Paolo. 1st A certificate signed by the Chancellor of the Municipal Corporation of the city of Notabile, by which it is attested that in the year 1803, the Noble Marchese Don Pandolfo Testaferrata was appointed first Jurat; 2nd A diary or almanac of Malta for the year 1805, in which among the several Government employees, Marchese Don Mario Testaferrata is referred to as President of the “Monte di Pieta” e di Redenzione, and Marchese Pandolfo Testaferrata as commanding officer of the Veteran’s company. 3rd A copy of the “Times” newspaper of the 13th March 1812, which contains a description of a levee held by H.R.H. the Prince Regent at Carlton House. Among the presentations that took place, that of “Marquis Testaferrata, of the Ancient Princes Capo di Ferro, Charge d’Affairs Maltese. The Marquis alluded to in that description is not the claimant’s ancestor but Nicola Testaferrat, who at that time repaired to London with a deputation of Maltese gentlemen, in order to obtain some improvements in the system of the local government. The designations given in that issue of the “Times” clearly bespeak their origin. 4th A passport, signed on the 5th July 1861, by “Wilford Brett, Acting Chied Secretary to Government” and issued in the name of Governor Sir John Gaspard Le Marchant. In this passport there are the following expressions: – “These are to request and require .to allow the Marquis Gio Paolo Testaferrata Olivier, Captain Malta Militia”; 5th A letter addressed by Sir Victor Houlton, Chief Secretary to Government, on the 22nd Ocotber 1868, to “Marquis G.P. Testaferrata Olivier” in which we read:- “His Excellency the Governor having considered it necessary that a person should be appointed for the purpose of perusing the pieces to be performed at the Theatre Manoel, I am desired to inform you that his Excellency has been pleased to appoint you to discharge that duty; 6th A letter addressed on the 21st July 1863, by Frederic Rogers, Esq., to Marquis Testaferrata Olivier and Commander Walter Strickland, R.N., which I to the following effect: – I am directed by the Duke of Newcastle to acquaint you that the Lords of the Committee of the Privy Council for Trade have forwarded to this office a letter addressed to that department by yourself and Captain Strickland, enclosing a programme of a proposed Exhibition of Maltese Industry, General Products, and Fine Arts; and I am directed, &c”; 7th A copy of the Malta Government Gazette, containing a list of persons deemed to possess the qualifications required by law in order to vote for the election of the members of the Council of Government for the Island of Malta. In this list the claimant is designated as “Testaferrata Olivier, Marquis Gio Paolo”. It is proper here to remark that, as in the memorandum by that gentleman it is stated that the prefix of “Marchese” was added to his name in pursuance of a decision, a copy of which was not produced by him, we are inclined to believe that the claimant alludes to some order which may have been given on the subject by the Commissioners charged with conducting the election of Members of the Council of the Government of Malta. But those Commissioners had certainly no power to give a title to a gentleman who had no right to bear it; 8th Lastly, a printed list of the different schools of the Lyceum of Malta, showing the names of the students to whom prizes had been awarded or who had distinguished themselves at the annual examinations, as well as the names of the teachers of the said schools. In that list we read: “School of History and Geography, under the direction of Marchese G.P. Testaferrata Olivier.”

But from information obtained in the course of our inquiry, it appears that when on the 9th September 1852, the claimant was appointed Captain of the Miitia, he was simply designated as G.P. Testaferrata; and that in official documents concerning public departments he was described with his baptismal and surname only, down to 1870, since which period the title of Marchese has been prefixed to his name.

(Considerations on further documents presented by said Lorenzo Cassar Desain)

After this detailed examination of the documents exhibited by G.P. Testaferrata Olivier, we now come to inquire into those produced by Lorenzo Cassar Desain, viz: 1st A passport issued on the 19th May 1857, under the administration of Sir William Reid. It runs thus:- “These are to request and require” “to allow the Marquis Philip James Cassar Desain, of the Royal Malta Fencible Regiment” .accompanied” “2nd Another passport issued in the name of the head of the Government, on the 17th June 1863, and conceived in the same terms which were used in the oen just mentioned; 3rd Two passports, issued from the Foreign Office on the 19th and 22nd Ocotber 1863. They contain the following expressions:-“We, John Earl Russell” “Her Majesty’s Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs”.request and require in the name of Her Majesty to allow the Lieutenant the Marquis Philip James Cassar Desain (British subject), of the Royal Malta Artillery.

The gentleman referred to in the above-named passports is the claimant’s father.

In connexion with these documents, we beg to state that the late Sir Giuseppe Vincenzo Testaferrata, brother of Pandolfo, the grandfather of the claimant Gio Paolo Testaferrata, was repeatedly mentioned in Government public acts. In six Government notices dated respectively the 16th and the 26th June 1817, the 1st January 1819, the 15th January 1820, the 15th January 1821, and the 15th January 1822, he is designated ‘Giuseppe dei Marchesi Testaferrata”, in twelve other notices of the 1st January 1823, 1824, 1825, 1826, 1827, 1828, 1829, 1830, 1831, and the 11th January 1832, the 1st January 1833, the 2nd January 1834, he is styled, in the English version of the Government Gazette, “Sir Giuseppe Vincenzo Testaferrata;” and in the Italian, “Cav. Giuseppe Vincenzo Testaferrata”.

In a notice which appeared in the Gazette of the 15th May 1833, announcing the appointment of that gentleman to the commandership of the order of St. Michael and St. George, we read the following expression: “Signor Giuseppe dei Marchesi Testaferrata”, in the Italian version, and the word “Marquis” in the English.

In a notice of the 29th May 1833, which contains an account of the ceremony of the investiture of the newly elected knights, he is called “Marquis” in the English version, and “Marchese” in the Italian. He is designated as “Cav. Giuseppe v. Testaferrata, C.C.M.G.” in the Italian version, and “Sir Giuseppe v. Testaferrata, K.C.M.G.” in the English, in five notices which appeared in the Government Gazette on the 2nd January 1835, the 1st January 1836, the 2nd January 1837, the 1st January 1838 and 1839.

On the other hand, Gilberto Testaferrata Viani, who like Sir Giuseppe v. Testaferrata, was not the first born descendant in the primogenial line of the family, was styled Marchese in twenty notices which contained his appointment as Lord Lieutenant in the years 1820, 1821, 1822, 1823, 1824, 1825, 1826, 1827, 1828, 1829, 1830, 1831, 1832, 1833, 1834, 1835, 1836, 1837, 1838, 1839.

We also found in several lists of the electors of the members of council of for Malta and Gozo, published under the Government authority, the said Gio Paolo Testaferrata referred to as “Marchese” in the list of electors for Gozo, and as “dei Marchesi” in the list of those of Malta. In some notices the late Francesco Gauci Bonici, who was for several years member of the Council of Government, is designated as Barone, which title had originally been granted to one of his ancestors, for the term of his natural life only. (Sua naturali vita perdurante).

The above stated circumstances lead us to conclude that no great importance was formerly attached by the Local Government to a proper use of the titles of nobility. In confirmation of this statement, we may mention that in several Government notices, the late Baldassare Sant was styled Count, to which title he had no right. His son and heir, Lazzaro Sant, does not claim but the titles of Conte and Barone Fournier de Pausier, which he inherited from his mother Luigia, wife of the said Baldassare, to whom they were not certainly communicable.

It must, however, be remarked that since 1870, the said Gio Paolo Testaferrata and Lorenzo Cassar Desain have been styled Marchesi in several Government Notices concerning the Agrarian Society, and the Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce.

With reference to the foregoing papers, by which the above-named claimants have attempted to establish the recognition of the title now under consideration, on the part of the British Government, we beg to refer his Excellency’s attention to the fact, that, as far as we are aware, such official documents emanating from the head of the Local Government and other authorities of the island, were not issued pursuant to orders received from Her Majesty or her predecessors, who are the source of all honours and distinctions.

(Considerations on certain authorities quoted by said Gio Paolo Testaferrata Olivier and said Lorenzo Cassar Desain)

We now proceed to submit out remarks on certain authorities quoted as already stated in the memorandums by G.P. Testaferrata and Lorenzo Cassar Desain, who seem to think that those authorities are sufficient to establish: -1st That the feudal laws recognize two sorts of fiefs, one termed “ad usum Francorum”, and the other “ad usum Longobardorum”: that the former are indivisible, their possession belonging to one person exclusively, such as those existing in the Kingdom of Naples; whilst the latter are divisible, pertaining to several persons jointly, “ut feuda Lomardiae, Etruriae, aliorumque Italiae partes versus montes”; 2nd. That it is a custom (which obtained throughout Italy) that the fiefs to which a dignity is annexed, that of Duke excepted, are divisible. 3rdly. That the principle according to which the fiefs are divisible with regard to the dignity annexed thereto, proceeds not from the common feudal law, but from a custom which prevailed in Germany, Lombardy, and in many parts of Italy. 4thly. That in Germany the sons of Counts and Marquises are likewise styled Counts and Marquises, and in Lombardy, the fiefs to which a dignity is attached are divisible, so that they descend equally to all the holder’s children; 5thly. That a dignity does not become divisible merely because all the children and descendants of the grantee actually enjoy it. 6thly That there are divisible fiefs with or without any dignity annexed thereto. 7thly. Lastly, that there are honorary and nominal titles, without any fiefs or other landed property to which they are attached.

We think that we have fully explained what the claimants had in view to establish by the authorities quoted by them. But those authorities will be found to be inapplicable to the question under consideration, if the present title was not recognized by the local authorities; and the applicability of most of them depends on the decision of the question whether that grant is to be regulated by the Sicilian feudal laws or by the custom prevalent at that time in Savoy.

If by that grant it was intended to raise Mario to the nobility of Savoy, we fully concur in the opinion that it is inheritable by all the grantee’s contemporary descendants. In Germany, in Lombardy and in other parts of Italy, including the Duchy of Savoy, a custom since a distant period obtained under which the titles of nobility that are annexed to fiefs (which in those countries are divisible), as well as those which are purely nominal, descend after the decease of a count or marquis to all his sons, who all assume the title of count or marquis, as the case may be. But if the succession to the grant is to be regulated by the feudal law which was in force in Sicily, considering that the title was created by a King of Sicily and registered in the Office of the Privileges of the Kingdom of Sicily, the consequence is widely different.

In Sicily, as a general rule, (admitting of course to some exceptions) fiefs are not divisible, and the joint possession of titles by more than one person is unknown in that country.

As an illustration of this fact, we beg to submit the following important quotations from eminent feudists. Cumja, a leading Sicilian writer on feudal law, “In capite si aliquem mortis num. 176 and 177,”says, “Sed in hoc nostro Sciliae Regno hodie non invenientur feuda dividua per Cap. Volentes. In fin. Secundum communem interpretationem, ibi feudo integro et indiviso perdurante, et etiam per istud C. Si alliquem, ubi ab intestate Francorum jure vivitur, ut discimus secundum communem intellectum in verbo Francorum. Unde hodie in hoc Regno, » ».quia feuda omnia individua sunt, et ille textus de dividuis loquitor ».

Octavius Corsettus, who is also a Sicilian feudist, Con. 23, Num. 2, observes, « Bene tamen verum est quod cum in Regno feuda sint indivisibilia ex dispositione constitutionis Divae Memoriae et capituli Volentes, et utrobique dicunt Doctores ad unum tantum est necesse quod deveniat corpus feudi illeque erit primogenitus masculus, ita dicunt passim nostrales », and in the second annotation appended to the said Consilium the author remarks, « Dignitatis feudum integre capiat primogenitus ».

In the Commentaries of Muta, on the “Capituli Regni Siciliae”, cap. 33, n.n. 96, 97, tom. I, the following passage is worthy of notice: “Ex hoc ex quodam jure medio succedendi in feudis, nam non mere vivimus jure Longobardo, ut dico in praedicto cap. Volentes. Ristrict, 2: etenim tunc succederent aequaliter omnes, omniumque esset feudum. (d. Cap. I. in principio de success, feudi) vel dividebant cum consensus imperiatoris, vel ex consuetudine inducta, scientibus et videntibus etiam Dominis ipsis Imperiatoribus, ut ait Iserniae in tit de feudo Marchioe, num 4 ».ubi quod in Lombardia omnes liberi essent. Marchiones (d. cap. Omnes Filii si de feud. Fuer. Controvers. Pietr. De Gregor. p. 4 q. I, n. 9). Etiam jure Francorum, ut dicam inferius, in versie. Quoniam vero: Sed est inter haec duo jura medium jus »..quod introducitur ex ipso Capitulo Volentes, ubi Etiam Dom. Fimia qui ait: Quod ex quo in feudorum successione vivatur quasi jure Francorum, nam feudum debet esse integrum et per consequens ad unum pervenire, id est ad primogenitum ex Iserniae doctrina, in tit. De natur, success. Feudi, in fin. Et de prohib. Feudi alienatione per Federici paragrapho Praetera » addo de S. Georgio d Feudis, in verbo Dux, fol. 8 et 9, n. 10, ubi tres assignat rationes. Primo quia ista feuda praesertim de Comitatibus, Marchionatibus, Ducatibus, etc. et sic in feudis et dignitatum..in tantum quod redigirentur ad nihilum, stante quia sunt regales et loquitor ipse se S. Georgio de Comitatibus etc Feudis Sabaudiae..Secunda ratio, dicit ipse, quia aliqua feuda, et ut plurimum omnia quae sunt nominata, et si dividerentur, perderent nomina et consequenter carerent fructu et effectu..aliam assignat rationem, eo quia talia feuda sunt (ut dixi) dignitates et dignitas est indivibilis. This last reason clearly shows that dignities or titles of nobility in Sicily are indivisible, and that their indivisibility is desumed from the indivisibility of feuds, and not e converso the latter from the former.

At num. 105 the learned Sicilian writer says: Immo ut sequar materiam in tantum hoc ampliat ipse Molina supra citatus (Molina de primogenitis, cap. 11, lib I. n. 10. cum seq) ut etiam procedat quando rex donanet alicui aliquod castrum sibi et suis descendentibus, cum titulo ducatus aut marchionatus, quia nihilhominus, mortuo concessionario, ad unum tantum transpire debeat, non obstante quod multi tenuerint contrarium.

These last words quod multi tenuerint contrarium employed by Muta, induced us to consult Molina, quoted by that writer, and the authorities referred to in his works. The writer De Primogeniis Hispanis, after having clearly explained their import and meaning, thus concludes: Ut autem de hac re perfecta resolutis habeatur, duae species diversissimae considerandae sunt: eut enim agitur de sola dignitate, quae quoad officium etadministrationem conceditur: aut enim de ea dignitate quae simul cum oppidis et territorio donate est.

In prima specie subdistinguendum erit, aut enim ea dignitas simpliciter alicui a principe concessa est, aut pro se et suis descendentibus ac successoribus. Si simpliciter ea dignitatis concesa fuerit, haec dignitatis concessio morte donatarii expirabit, nec ad primogenitum nec caeteros filios nex haeredes transitoria erit..Si vero ea dignitas alicui pro se ac suis descendentibus concedatur, tunc ad haeredes et successores transitoria erit, ut superius ostendimus. In hoc autem casu, dignitas ipsa, jusque in ipsa dignitate succedendi individuum erit, primogenitoque solo pertinebit. Est tamen regulare ut quoties similes dignitates sint ad haeredes transitoriae, non ad omnes filios sed ad primogenitum tantum, pertinere debeant Dignitates nempe hujusmodi sive in feudum, sive libere concessa sint, simper individuae ese debent .idque si ad solius dignitatis jus referatur, verissimum est, nisi consultudine contrarium sit observatum. Tunc enim omnes filii, Duces Comites et Marchiones vocabunter, prout in Italia et Allemania observari solet. .quae consuetudo numquam in Hispania (to which may be added numquam in Sicilia) observata fuit, et in hac specie nulla est inter scribentes Hispanos controversia.

In secunda specie, ubi scilicet cum ipsa dignitate, proprietas territorii seu castra ac oppida concessa sunt, se offert opinionum varietas, de qua superius mentionem fecimus. Prima, quod haec bona libera sint judicanda, secunda opinion, quod ea bona majoratu subjecta censenda sunt. In hac autem opinionem varietate secunda ea bona majoratu subjecta censenda sunt. In hac autem opinionum varietate secunda opinion mihi probabilor videtur etc (L.I. c. XI. N. 21 et seq.) To this conflict of opinions Muta alluded by his expression quod multi tenuerint contrarium.

Nor is there any difference between the purport of the expressions all the descendants contained in the patent of creation of this title, and that of the word descendentes which occurs in the foregoing quotations.

Cardinal De Luca in his treatise De Feudis, dis. 115. n. 11, observes much to the point: Et quamvis scribentes pro actoribus, in eo insisterint, quod voluntas dicenda potius esset clara, dum investitura cantat de descendentibus masculis in genere, et in numero plurali, de sui natura apto comprehendere omnes, idque apud judices primae instantiae plausum habuerit; attamen id pro meo sensu continebat potius levitatem, nimiumque debile fundamentum videbatur, quoniam vocabulum omnes apponitur ad denotandam habitualem capacitatem, et comprehensionem omnium de illo sanguine vel genere, compatibiliter tamen cum restrictione ad majorem natum seu primogenitum, circa actum, seu eo modo, quo in jure patronatus vel praesentandi, alliisque similibus, passim habemus. Et in his terminis feudalibus comprobat actualis praxis investiturae feudorum in Regnis utriusque Siciliae quod cantat pro se et haeredibus ex corpore descendentibus, ideoque omnes habitualiter vocati sunt. Et tamen actualiter successio inter eos defertur jure singulari, et cum ordine primogeniturae.

(Decision of the Commissioners)

In concluding this part of our Report, we beg to state that after a full and impartial examination of all the circumstances of the case, and of the numerous documents which have been produced, we are of the opinion that the claimants have failed to establish their right to the title, and their names therefore will not be inserted in the list of titled gentlemen appended to this Report.

Some of the above claimants to this title pursued their claims to the title. They were joined by other new claimants. The list of undeterred claimants is as follows: Emmanuele Testaferrata Bonici, Enrico Testaferrata, Lorenzo Antonio Testaferrata, Luigi Testaferrata, Ignazio Testaferrata, Carmela Testaferrata, Giuseppe Apap Testaferrata and Francesco Gauci Testaferrata. Testaferrata Bonici claimed the title for himself exclusively whilst the others claimed that the title is to be borne by all of the contemporary descendants of the grantee indiscriminately. In 1883, a Committee of five Titolati recommended that the title be enjoyed by the eldest son of each subformation. The recommendation of the majority to the British Secretary of State for the Colonies reads as follows: This grant (of 1717) not being a feudal concession its inheritance cannot be governed by the same laws that obtain with the feudal titles (sic.!) granted to and possessed by the generality of the Maltese nobility, and no feudal laws can be invoked except by analogy, either to restrict the designation of Marchese, as derived from this diploma, to the primogenial line of the grantee exclusively, or to extend the same to all his contemporary descendants. Owing to these facts the Committee thinks that similar claims can be satisfactorily settled through an examination of such official documents as the claimants may produce and prove thereto the possession of a title of nobility acknowledged on the part of the Grand Masters in the male ancestors of each claimant. In claims so established, as has been the case with those already examined in paragraphs 37-40, it is desirable that the title should be allowed under the definitive rule that its descent be limited to the eldest son in each case, and that their names be placed in the official list of Titolati according to the date of the first recognition of the title in each respective line. We humbly beg to submit that after a most careful examination that no other advice on this part of the Committee could be effectual with regard to claims exclusively based on the diploma of King Victor Amadeus, as against the claim preferred by Emmanuele Testaferrata Bonici. This recommendation does not appear to have been accepted by the Secretary of State for the Colonies. See:- Report of the Committee of Privileges of the Maltese Nobility on the claims of certain members of that body with the Secretary of State’s Reply, August 1883, presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty (C-3812). (See Doc. 1. Report Paras. 37-40; and Doc. 2 Reply).

* Title of Marchese di San Vincenzo Ferreri (1716/1725).

The title of “Marchese di San Vincenzo Ferreri” is stated to have been one of the most “conspicuous” titles of nobility in Malta. The date of creation is invariably given as 1716 in favour of Mario Testaferrata (already a Knight of the Holy Roman Empire). The grant states it was granted “in dicto Regno Neapolis” by Philip of Spain as King of “Legionis Utriusque Siciliae” on the 10th November 1716.

The title has been the subject of many issues. An act of disinheritance of 1758 by the grantee ordered that the title be succeeded by his second son. In 1901, after the incorporation of the Neapolitan Crown into that of a United Kingdom of Italy, it was discovered that the title itself was null and void. Towards the end of the 20th century an argument was put forward saying that it is a Maltese title first created in 1725.

ORIGIN AND NATURE OF TITLE

The title of “Marchese di San Vincenzo Ferreri” was conferred in the Kingdom of Naples by Philip V, King of Spain and of Naples upon Mario Testaferrata, a Maltese, by a patent dated the 10th November 1716, registered in a book called “Privilegm Neap. X. fol. CCLVIII”. The following is an extract from that patent: “Tenore igitur praesentium ex certa scientia, regiaque auctoritate nostra, deliberato et consulto, ac ex gratia speciali maturaque sacri nostril Supremi Consilii accedente deliberatione, praefatum Don Marium Testaferrata, Sacri Romani Imperii equitem Tornearium, et cujus patria est insula Melitana, Illustrem Marchionem, in dicto Regno Neapolis Sancti Vincentii Ferreri ejusque haeredes et successores ex suo corpore legitime descendentes, praedicto ordine successivo servato, dicimus creamus et nominamus, ab aliisque in omnibus et quibuscumque actis et scriptures dici et nominari olumus et perpetuo reputari jubemus”

Gauci (1981) describes the title created in 1716 as having been succeeded by his son Enrico (2nd), in turn by the latter’s son Daniele (3rd), in turn succeeded by the latter’s son Gregorio Augusto (4th) in turn succeeded by the latter’s son Daniele (5th) in turn succeeded by the latter’s son Emmanuele (6th) in turn succeeded by the latter’s son Daniele (7th), in turn succeeded by his eldest son Alfio (8th).

There is no record of formal registration of the title of Marquis of San Vincenzo Ferreri. According to the Report of a Royal Commission published in 1878, it was explained that the title was acknowledged in the person of the grantee Mario Testaferrata by Grand Master Manoel de Vilhena. The Report states that the Grand Master issued on the 30 April 1725 an order outlawing the use of the noble titles of Illustrissimo and Nobile but amended it by subsequent decrees dated 11 May 1725 and 9 July 1725. By that third enactment the Grand Master also excepted Mario Testaferrata calling him “Marchese di San Vincenzo Ferreri”. (“S.A. Sema Padrone, ordine e commanda che nella suddetta Prammatica s’intende eccettuato il Marchese di San Vincenzo Ferreri Don Mario Testaferrata, e li suoi discendenti. Oggi li 9 Luglio 1725. Ita referent. – F.N. Nalvanus de Vajus, AUD”). The Report concluded that this act was sufficient for establishing a direct recognition of the title of Marchese di San Vincenzo Ferreri. The Report classified this title under the list of titles granted by foreign sovereigns during the Government of the Order of the Knights of St. John.

The title is not Spanish. As seen in the case of Marquis De Piro, according to Spanish law (Ordinance of Philip IV), any person who is to be raised to the dignity of Marquis or Count must be previously created Viscount, which title is to be subsequently suppressed. Testaferrata was never created Viscount. The grant of San Vincenzo Ferreri says that it was granted in the Kingdom of Naples. In conclusion the title is Neapolitan and is therefore regulated by Neapolitan law. Therefore the terms of succession cannot be changed unless with the assent of the Neapolitan sovereign. It follows that the Sovereign of Malta had no right to change the terms of succession imposed by the king of Naples.

NULLITY OF TITLE

This conclusion was clouded in 1901. In that year Emmanuele Testaferrata Bonnici attempted to be recognized by the king of the newly unified Italy. However, his request was turned down because the king realized that the title had been granted by a non-existent king of Naples (“il napolitano non era piu’ nel dominio del Re di Spagna”, decision 28 May 1901 Italian Consulta Araldica no. 2408 – See Gauci, 1992).

In fact, by the terms of the Treaties of Utrecht (1713) and Baden (1714) Spain had lost both of the “Two Sicilies”:- Naples to the Austria Emperor and Sicily to the Duke of Savoy.