Barons di Budaq (Budacco) 1398, 1644, 1646, 1716.

Last Update: 26-04-2023.

Granted to: Nobile Johannes d’Aulesa.

By: Mary I, Queen of Sicily and Malta and Martin I, King of Sicily and Malta.

On: 1398 at Palermo.

With Remainder to: His descendants by feudal tenure (Jure Francorum) in perpetuity.

List of Title holders:

1. Nobile Johannes d’Aulesa, 1st Barone, revoked and executed 1398.

Granted to: Dr Niccolo Cilia MD.

By: Jean Paule Lascaris de Castellar, Grand Master of Malta.

On: 1644 at Valletta.

With Remainder to: His descendants by feudal tenure (Jure Francorum) in perpetuity.

List of Title holders:

1. Dr Niccolo Cilia MD, 1st Barone, (d. 1646), extinct.

Granted to: Cesare Passalacqua, Genovefa Passalacqua Fiteni and Silvestro Fiteni.

By: Jean Paule Lascaris de Castellar, Grand Master of Malta.

On: 1646 at Valletta.

With Remainder to: Their descendants by feudal tenure (Jure Francorum) in perpetuity.

List of Title holders:

1. Sig. Cesare Passalacqua, Genovefa Passalacqua Fiteni and Silvestro Fiteni, 1st Holders (Barone /Baronessa), extinct.

Claimants:

1. Nobile Giovanni Fiteni, deJure 2nd Barone, succeeded by his son.

2. Nobile Silvestrino Fiteni, (d. 1709), deJure 3rd Barone, succeeded by his sister.

3. Nobile Valenza Fiteni Falzon, (d. 1721), deJure 4th and last Baroness, gave up claim in 1716.

Granted to: Dr Gio Pio de Piro JUD.

By: Ramon Perellos y Rocaful, Grand Master of Malta.

British Crown Recognition: 1878.

On: 1716 at Valletta.

With Remainder to: His descendants in perpetuity each holder of the title having the right to nominate a successor. In default of nomination to the first-born male descendant and in absence of male issue, to the first-born female descendant. Members of the clergy are precluded from succeeding by primogeniture.

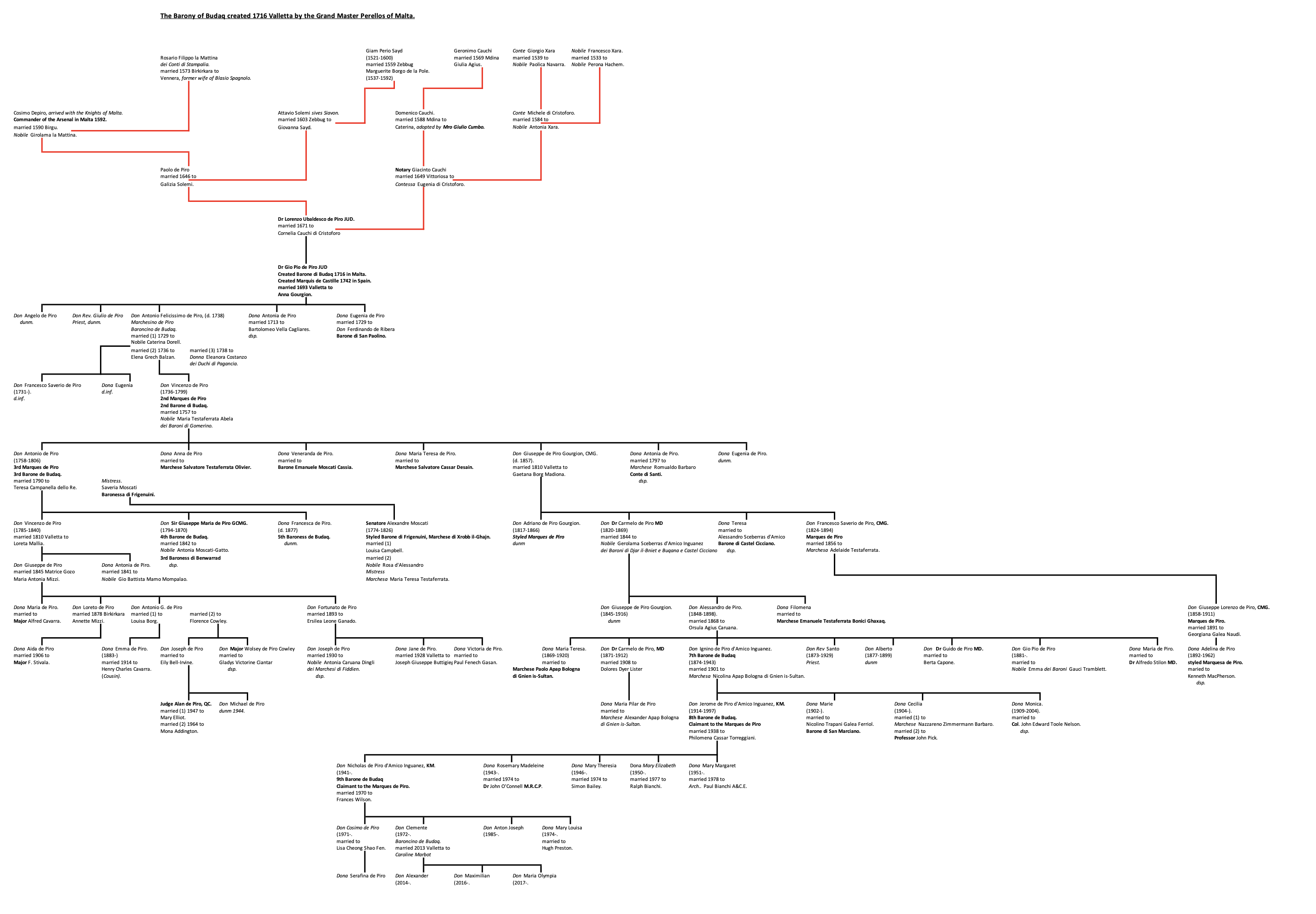

List of Title holders:

1. Dr Gio Pio de Piro JUD, (d. 1752), 1st Barone, succeeded by his grandson.

2. Don Vincenzo de Piro, (. 1799), 2nd Barone, succeeded by his son.

3. Don Antonio de Piro, (d. 1806), 3rd Barone, succeeded by his son.

4. Don Sir Giuseppe Maria de Piro, GCMG, (d. 1870), 4th Barone, succeeded by his sister.

5. Dona Francesca de Piro, (d. 1877), 5th Baronessa, succeeded by her first cousin’s son.

6. Don Giuseppe de Piro Gourgion, (d. 1916), 6th Barone, succeeded by his nephew.

7. Don Igino de Piro d’Amico Inguanez, (d. 1942), 7th Barone, succeeded by his son.

8. Don Jerome de Piro d’Amico Inguanez, (d. 1996), 8th Barone, succeeded by his son.

9. Don Nicholas de Piro d’Amico Inguanez, (1941-, 9th Barone.

Heir (title is disposable by nomination in the titleholder’s will to any of his children or grandchildren or his eldest son): Don Cosimo de Piro d’Amico Inguanez, (1971-, Baroncino di Budaq and styled as Marchesino de Piro.

Articles relating to this title:

Footnote: The title of “Barone di Budack” was conferred by Grand Master Perellos, by a diploma of the 23rd April 1716, on Gio Pio De Piro The title is purely nominal and does not have any property attached to it. In their general observations, the Royal Commissioners observed that most of the titles granted by the Grandmasters were merely honorary and had no relevance on property tenure “although it appears that those titles (granted by the Grand Masters) have derived their different denominations from several feudal lands existing in these islands, this annexation, however, is in most cases purely nominal, for those lands were never in reality conveyed to the grantees, but they remained as they are still Government Property.” The Commissioners also identified the only three exceptions to this purely nominal phenomenon, where tenure of property was a prerequisite namely Bahria, delle Catene, and Senia, the last being a divisible property. See:- “Correspondence and Report of the Commission appointed to enquire into the claims and grievances of the Maltese Nobility”, May 1878, presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty (C.-2033.) (See Report Paras. 82).

Published sources show this title as having been conferred on Gio Pio with power given to him and his descendants of nominating a successor, and in failure of such nomination with automatic transmission to the first born descendant. What the said sources tend to omit is that the latter transmission is qualified by the grant in the sense that such first born should be the first born descendant of Gio Pio De Piro from his wife Anna Gourgion, thereby excluding any issue (if any) from a different mother. (See:-“Correspondence and Report of the Commission appointed to enquire into the claims and grievances of the Maltese Nobility”, May 1878, presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty (C.-2033.) (See Report Paras. 27-28).

The Royal Commissioners decided not to express any opinion on this title saying that the title was contested and that it would be prudent not to hear the claimants. The Commissioners did however go as far as outlining the history of this title and the validity of the 1716 grant. “Correspondence and Report of the Commission appointed to enquire into the claims and grievances of the Maltese Nobility”, May 1878, presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty (C.-2033.) (See Report Paras. 27-28).

Altogether the Grand Masters created six titles which are disposable by nomination, namely Gomerino (Perellos), Budack (Perellos), San Marciano (Vilhena); Tabria(Vilhena), Culeja (Despuig) and Benuarrat (Despuig).

The actual report says the following:

“The second in the committee list, according to the antiquity of the patent of creation is that of the title of ‘Barone di Budack’ conferred by the same Grand Master Perellos, by a diploma of the 23rd April 1716. The grant was made to Gio Pio De Piro and to one of his issue male or female in perpetuum. The fief ‘ta Budack’, which is of very old erection, had been granted to the Proto Medico Nicolo Cilia, by whose death it had reverted to the Crown, but it was, by a patent of the 22nd December 1646, reconferred, by Grand Master Lascaris De Castellar, upon Silvestro Fiteni, on whose death it again fell back to the Principality.

It was lastly for the third time granted, by the abovementioned patent of the 23rd April 1716, to Gio Pio De Piro, and to such of his descendents as the last holder should name, and, in default of nomination, to the first born child, not being a member of the clergy, secular or regular. The terms of the grant are nearly identical with those of the preceding patent of the title of Barone di Gomerino. “Tibi Joanni Pio De Piro et post tui obituum uni ex filiis velfiliabus legitimis et naturabilibus, ex te et Nobili Anna Gourgion tua conjuge procreatis velprocreandis quem vel quam omni futuro tempore et in perpetuum. Tu et quilibet seu quaelibetex tuis successoribus in dicta Baronia constitutus seu respective constituta, malueritiseligendum vel eligendam, tribuimus, concedimus et donamus hujusmodique titulo insignimusac Baronem dicto Feudi de Budacco constituimus et ita nominari posse et debere….Hoc etiam addito, quod in casu tui vel tuorum in infinitum decessus, absque ulla nominatione velelectione dictui tituli seu Baroniae, ex nunc censeatur nominatus et electus Primogenitus,nisi erit ad sacros Ordines promotus et in Religione professus, et in defectu marium foeminaprimogenita….

The only gentleman who claims this title is Monsignor Don Salvatore Grech Delicata, a lineal descendent of Gio Pio De Piro, and nominated to the succession of the title by the last holder of it, Baronessa Francesca De Piro. Although not other person has appeared to claim the present title, Giuseppe DePiro, however, who is also one of the descendents of the original grantee, has laid before the Commission an oppository nota accompanied by several documents, calling in question Monsignor Delicata’s claim, and contending that the title of “Barone di Budack”, having since a long time become extinct, the estate annexed thereto had devolved upon him by the title of a Primogenitura.

We have taken no notice of the documents produced by Giuseppe De Piro, nor have we called for information from Monsignor Delicata, for the same reasons for which we had not asked the two claimants of the title of “Barone di Gomerino” to appear before the Commission; consequently we pronounce no opinion as to the justice of Monsignor Delicata’s claim, nor will his name be included in our list; the decision of that claim being thus left to the competent authority.”

As predicted by the Commissioners, a court action was leveled by Giuseppe De Piroagainst Monsignor Grech Delicata. However, it should be remarked that contrary to what was indicated in the report the issue did not concern the title per se (although the possession of the title had some bearing on the outcome of the case) but more on who was to succeed an entail the commencement thereof was to start upon the extinction of the title of Budack. The judgment given by the Court of Appeal (Judges Dingli, Xuereband Vella) is dated 7 January 1885 and although not in published is available at the Archives of the Maltese Courts.

Giuseppe De Piro claimed that Gio. Pios father (Lorenzo Ubaldesco) set up an entail/”usufruct” by means of a deed made in the acts of Notary Gaspare DomenicoChircop of the 30 April 1717, whereby the usufruct of certain properties were to be enjoyed by the possessor of the title granted in 1716 with the proviso that should Gio. Pio’s descendants no longer enjoy that title, then the properties would be erected into a majorat stemming from the same Gio Pio preferring all agnatial descendants to female descendants. Giuseppe Depiro further claimed that although Gio Pio was duly invested, his successor and the latter’s descendants (namely Antonio De Piro, Vincenzo Depiro, Antonio Depiro the junior and Giuseppe Maria Depiro) were never so invested and never paid relative homage consisting of two guns and that although each one of them abusively (“abusivamente”) used that title, they enjoyed the properties not by virtue of the 1716 barony but by virtue of the 1717 deed. Thus, Giuseppe De Piro (the plaintiff) claimed that upon Giuseppe Maria Depiro’s death in 1870, the properties were in terms of the 1717 deed to be enjoyed by him as the seniormost agnatial descendant in the descent from Gio Pio Depiro. However, the plaintiff said that he was in possession of this entail because the said Giuseppe Maria Depiro in the erroneous belief that he could nominate a successor, nominated his sister Francesca. Moreover the said Francesca (who died in 1877) by means of her wills nominated Monsignor Grech Delicata as her successor thereby putting the latter in possession of the properties. Finally, GiuseppeDepiro claimed that in any event the said Francesca could not nominate because she was mentally infirm. Moreover Giuseppe Depiro made a further claim that the Barony fo Budack like all other titles ceased to exist by virtue of a law enacted by the Government of the French Republic which abolished all titles.

For these reasons, Giuseppe Depiro requested the court (1) to annul the nomination in favour of Monsignor (2) to declare that on the death of Giuseppe Maria in 1870, that the entail devolved in his favour by virtue of the 1717 deed and that Francesca held the properties unlawfully and (3) to order the Monsignor to make refunds according to law.

On the other hand, the Monsignor argued that the enjoyment of the barony was not affected by the non-payment of homage was no obstacle to the succession of the title and that Francesca was mentally capable.

It is to be remarked that the court only considered a genealogical table which was exhibited by the parties showing that Giuseppe Depiro was descended in the primogenial line from Gio Pio only through Antonio and Vincenzo and thereafter he was descended from Vincenzo’s second son Giuseppe and from Carmelo son of the said Giuseppe, whilst the Monsignor was only descended from the said Vincenzo’sdaughter’s daughter.

The court of first instance dismissed Depiro’s claim that the title ceased to exist because of non-fulfilment of payment of homage also adding that the requirement of investiture ceased to be observed by reason of desuetude i.e. disuse. Moreover the Court held that the Decrees of the French Republic were never observed and that the successors of GioPio Depiro were always recognized as Barons of Budack. The court also held that the fact that Francesca erroneously believed that the 1717 deed empowered her to nominate did not invalidate the nomination made under the 1716 grant. The Court thus rejected Giuseppe Depiro’s demands altogether. An appeal was lodged and new documents were exhibited.

The Court of Appeal observed that the solution to the issue rested on six points, namely:

1. whether the nomination made under the erroneous impression that the 1717 deed allowed a nomination to be made, invalidated such nomination;

2. Whether the nomination made by Francesca was valid despite the Decrees of the French Republic which abolished all titles of Nobility in Malta (thereby implying the commencement of the majorat);

3. Whether the non-investiture and non-payment of homage by Francesca was tantamount to an unlawful possession of the title;

4. Whether the faculty to nominate a successor in the title excluded members of the clergy;

5. (A procedural plea) whether the plaintiff could exercise the action as he did; and

6. Whether or not Francesca had her mental capabilities.

a. In regard to the first question, the court of Appeal held that despite the error, the nomination was valid: e’ evidente che amondue I successive testatori volevanoesercitare ed esercitarono, uns facolta’ che realmente avevano, e le nominee daloro fatte con tale facolta’, non possono essere ritenute come nulle, o altrimentiinefficace. non essendo necessaria, per la validita della nomina, la citazione diquesta Bolla

b. In regard to the second question the court of appeal held that the French decrees had no effect because in 1800 Malta reverted to its rightful owner the King of Naples: La cessione, quindi, che il Gran Mastro e I Cavalieri di S. Giovanno fecero il 12 Giugno 1798, alla Repubblica Francese, non aveva, come tale, alcun effetto legale; poiche subito che essi abbandonarono Malta e le altredue isole, questi ritornarano al Re di Napoli, some successor di Carlo V nelRegno delle Due Sicilie

c. In regard to the third question, the court of appeal held that the payment of homage was not necessary for the enjoyment of the title, also adding that the requirement of investiture ceased to be observed by reason of desuetude: l’obbligo di chiedere l’investitura e di fare omaggio non era nella Bolla del GranMaestro imposto sotto pena di decadenza del titolo’.e sotto il Governo successivo,l’obbligo medesimo ando’ completamente in disuso rispetto a tutti I titoli di nobilta’conceduti dai Gran Maestri

d. In regard to the fourth question, the court of Appeal held that although a priest was excluded from the automatic succession, there was nothing in the grant prohibiting the nomination of a priest: Una restrizione colla esclusioneassoluta del prete, non sarebbe conciliabile col senso naturale delle parole cole quail la facolta’ fuq accordata ‘quem vel quam malverit eligendum vel eligendam’

e. In regard to the fifth question, the court of Appeal held that there was no need to ask for an annulment of all of Francesca’s wills but it was sufficient to demand the court to scrutinize only those parts of the wills which have a bearing on the title and entail, the other parts being of no legal interest to the plaintiff: a torto pretende il convenuto che le altre parti di quella domanda non possono esseresostnute per mancanza di citazione di quegli eredi I quail nella Baronia di cui sitratta non hanno alcun interesse;

f. On the sixth question, the Court of appeal heard that Francesca “non era capace di comprendere la lettura di una novella o di una comedia di Goldoni” (sic.!) and proceeded thereafter to examine the reasonableness of Francesca nominating somebody who albeit related was not descended in the agnatial line from Gio Pio DePiro.

The Court of Appeal gave much importance to the consideration that “l’oggetto delladisposizione nel caso presente non era un lascito di una cosa di poco momento che avessepotuto essere data a chichissia senza dare torto ad alcuno, ovvero senza privarne alcuno ilquale avesse ragionevole motivo di aspettarsela. E un titolo di nobbilta’ conceduto dal GranMaestro a Gio Pio De Piro, pel lustro di lui stesso e della sua famiglia, e dotato dal padre dello stesso Gio Paolo pel decoro della stessa famiglia nella persona del possessore, con usufrutto di beni i quali erano stati dal padre medesimo, insieme con altri irrivocabilmentedonati a tutti I suoi figli.” The Court eventually declared Francesca mad.

The Court of Appeal decided as follows:

“Dichiarando nulla la nomina del convenuto alla Baronia di Budach, fatta, sotto nome diprimogenitura o di primogenitura e baronia dalla Baronessa Francesca Depiro coitestamenti del 20 April 1874 e del 13 Novembre 1875, e implicitamente confermata col altrotestamento del 12 agosto 1875 e cio’ per incapacita’ della baronessa medesima, per infermita di mente da prima del detto mese di Aprile 1874 fino dopo l’altro mese suddetto diNovembre 1875; Confermando l’appellata sentenza inquanto rigetta la domanda dell’ attoreper una dichiarazione di essere stata la Baronessa, dalla morte di suo fratello, il BaroneGiuseppe Maria Depiro, illegitima posseditrice dei beni sui quali la Arcidiacono Depiroaveva costituito una primogenitura; – E condannando il Convenuto a rilasciare all’ Attorequegli stessi beni, ai termini (etc.)”

Given the fact that both courts noted that the genealogical table in the acts was only one showing the respective descent of Giuseppe Depiro and Monsignor Grech Delicata, it can only be said that the court (correctly) found Giuseppe Depiro to be in a more senior line to Monsignor Grech Delicata. One cannot surmise from this judgment that Giuseppe DePiro was necessarily the seniormost descendant Gio Pio Depiro.

Undoubtedly however, this judgment clarified the issue regarding homage and investiture.

In any event, it is unlikely that one will ever encounter a situation similar to that of the unfortunate Francesca. This is being said because :

a. the succession of properties under entail was revoked by the ENTAILED PROPERTY (DISENTAILMENT) ACT (ACT XII of 1950). Unlike the DISENTAILMENT OF PROPERTY (EXTENSION TO FIEFS) ACT (ACT XXX of 1969), there is no provision in this ACT for titles of nobility. Thus, after 1950 the property entailed by Lorenzo Ubaldesco Depiro in 1717 came to be held like any other property.

b. Although the Gieh ir-Repubblika Act (ACT XXIX of 1975) withdrew all recognition of titles of nobility, it cannot be said that the title is extinct;

c. In any event, today it is no longer possible to effect any nomination. In the Gieh ir-Repubblika Act (ACT XXIX of 1975), the law dictates that it is “the duty of every public officer or authority and of every body established or recognised by law and of every member thereof, to refrain from recognising in any way, and from doing anything which could imply recognition of, any title of nobility”. A similar duty is imposed in regard to other foreign honors’ which have not obtained approval by the local authorities. By reason of this ACT, it is therefore legally impossible (an offence?) for any notary to receive an instrument by which somebody can be ‘nominated’ to succeed a title simply because such nomination would be made contrary to law. It therefore reasonable to assert that it is impossible for any ‘possessor’ of the aforesaid title to make use of the faculty to nominate a successor.

It follows that one may disregard any ‘nomination’ purportedly made at any time after 1975, and instead follow the general remainder of the grant.

According to the Code de Rohan of 1783, a primogeniture is a regular individual entail consisting of chattels which devolved from first-born to first-born in the descendentalline. It can pass on to collaterals, the determining criteria operating in the following order: line (the first line excluding all the others), degree (the closer degree of relationship excluding the remoter) sex (the male sex being preferred to the female), and age (the elder being preferred to the younger). Accordingly, it follows that regardless of any nominations that may have been made in the meantime, in terms of the grant made out to Gio Pio De Piro, any succession happening after 1975 should be reckoned in accordance with the primogenial descent from Gio Pio De Piro and his wife Anna Gourgion.

* WAS NICHOLAS CILIA EVER THE ‘BARON OF BUDAQ”?

The fief of Budacho (Budaq) is situated in Malta rising uphill from Salini to Naxxar, and precisely near the beginning of the hill known as ‘Ta’ Alla u Ommu’. A title of “Baron of Budack” (Budaq) was created in 1716. However, other publications maintain that an earlier barony was created in the 17th century in favour of Nicolo’ Cilia. In this section, we examine the veracity of that claim.

In Gauci’s 1992 publication (page 65) we find this fief described as a Barony, viz “Baron of Budaq”. This is the description:-

Granted to: Dr. Niccolo’ Cilia, Protomedico; By: Grandmaster Jean Paul de Lascaris Castellar; On: 24th February 1644; Feudal Tribute: A bouquet of roses on Easter Sunday every year. Note: Niccolo’s father, Francesco Cilia, had purchased the fief of Budaq from Baron Antonio Inguanez on 16th May 1590. For some reason however neither father nor son ever paid homage to the grandmaster as an acknowledgment of fealty and were consequently never styled Baron. Niccolo’ was in danger of having his fief confiscated by the Order. However, he successfully petitioned the Grandmaster to be formally recognized as the Baron of Budaq. Cilia died on 29th August 1646 leaving no successor, whereupon the fief devolved to the Order to be regranted a few months later.”

This is by and large, a repetition of what is stated in Montalto’s 1978 book (page 106), which reads as follows:-

“The first protomedico to be ennobled was Nicolo Cilia, who in 1633 had been appointed to this office. He was probably also awarded the Croce d’Oro on his appointment. Cilia, however, had not been aware that he possessed feudal territory (fo which he had not paid homage), when he inherited the fief of Budach. His father Francesco, had bought the lands from Baron Antonio Inguanez for the sum of 2280 onze. The sale had been made on the 16 May 1590, and was registered in the acts of Notary Enrico Zarb. When the protomedico realized that he held feudal territory he wanted to be invested in order to acquire the title and to hold a legitimate claim for his fief. Grand Master Lascaris acceded to Cilia’s request and concluded a transaction with his protomedico, but only over a part of the fief. On the 18 February 1644, the Council of the Order had given the Grand Master permission for the said transaction. After eight days Cilia was created Baron of Budach, only two years before his death in 1646. There is no evidence that Cilia had been ennobled because of his service to the Order, but his appointment as protomedico probably had considerable influence in his investiture as Baron, since Lascaris could have reclaimed this fief in virtue of Cilia’s omission to pay homage.”

Both Gauci and Montalto refer to N.L.M. 1226, p. 435

On a closer reading, we notice a difference in the versions recounted by Gauci and Montalto. The former implies that Cilia was well aware of the nature of the ownership and ‘only’ suffered the minor inconvenience of not being styled Baron. On the other hand the latter says that it was only after the purchase that Cilia discovered he had bought a mere fief, not the full ownership, therefore standing to lose the property, because of non-compliance with the rule of investiture.

The marginal note reads “Oath and homage of the Magnificus Nicolaus Cilia in respect of the fief of Budacho”.

No title is mentioned.

Therefore, the claim that a barony was created in favour of Nicolaus (Nicolo) Cilia is not supported by the text of document 1226, p. 435.

We have also learnt that the grant of a simple fief did not give rise to a title of ‘Baron’.

So far, the only document showing that a title of “Baron of Budaq” was ever created is that dated 23 April 1716 in favor of Gio Pio De Piro. De Piro received only the title. The title of “Baron of Budaq” was separate from the lands of Budaq. We also know that the Depiro family never possessed those lands. One of the claimants to that title is on record for having stated that:

“Although the De Piro family enjoys the Barony of Budaq, there is not, however, any property attached to it in that neighbourhood.” http://multimedia.josephdepiro.com/DOCUMENTS/Biography%20English/IntroEngBiog.htm#Introduction

We find a similar circumstance in 1737 in the case of “Baron of Gomerino” when the holder of the property (Fabrizio Testaferrata, who was holding the property of Gomerino since 1713) was not holding the Barony which was being held by the possessor of an entail (Ercole Martino Testaferrata, who was holding the entail since 1734).

Thus, the holder (Cilia) of the property of Budaq was not the baron whilst a person who did not hold that property (De Piro) was entitled to the barony.

So when did the Cilia claim arise? In the 1878 Commissioners’ Report (para. 27) on the title of 1716 “Barone di Budack” we find the following observation:

“The fief ‘ta Budack which is of a very old erection, had been granted out to the Proto Medico Nicolo Cilia, by whose death it reverted to the Crown”

The 1878 Report is not saying that Cilia held the title of “Baron of Budaq”. All that it is saying is that he held the fief. Elsewhere, the Report (paras. 84-95) goes on to say that the tenure of a simple fief did not give rise to the title of a baron, observing that even the designation Magnificus in a grant did not give rise to a title. The Report allowed a simple fief to be regarded as a barony only if the Grand Master recognised this in a subsequent act.

Concluding, unless another document is produced, we cannot regard Nicolo Cilia as the “Baron of Budaq”even though he possessed those lands (or only part of them, as stated by Montalto).

Sources:-

- [29-33] A propósito de la soberanía mediatizada de la Orden de Malta, un

título de Castilla concedido en 1742 a un barón maltés: el Marquesado de

Piro, por el Dr. Marqués de la Floresta

https://cuadernosdeayala.com/portfolio_item/cuadernos-de-ayala-89/ Correspondence and Report of the Commission appointed to enquire into the claims and grievances of the Maltese Nobility, May 1878, presented to both Houses of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty (C.-2033.)

Charles Gauci “The Genealogy and Heraldry of the Noble Families of Malta VOLUME TWO ” (PEG Publications, Malta, 1992) ASIN: B0018V7SUA

Montalto, John, The nobles of Malta, 1530-1800 Midsea Books, Valletta, Malta : 1979 ASIN: B0000EE028

Copy of 1226, f. 435 http://cilialacorte.com/CERTIFICATE-GIFS/baroncilia.gif (reproduced above)

Alexander Bonnici O.F.M. Conv., “Giuseppe De Piro, 1877 (1933), Founder of the Missionary Society of Saint Paul”, Translated by Monica De Piro Nelson, Missionary Society of St. Paul, 1988 http://multimedia.josephdepiro.com/DOCUMENTS/Biography%20English/Introduction